The name Lucas (Luke) is probably an abbreviation from Lucanus, like Annas from Ananus, Apollos from Apollonius, Artemas from Artemidorus, Demas from Demetrius, etc. (Schanz, "Evang. des heiligen Lucas", 1, 2; Lightfoot on "Col.", iv, 14; Plummer, "St. Luke", introd.)

The word Lucas seems to have been unknown before the Christian Era; but Lucanus is common in inscriptions, and is found at the beginning and end of the Gospel in some Old Latin manuscripts (ibid.). It is generally held that St. Luke was a native of Antioch. Eusebius (Church History III.4.6) has: Loukas de to men genos on ton ap Antiocheias, ten episteuen iatros, ta pleista suggegonos to Paulo, kai rots laipois de ou parergos ton apostolon homilnkos--"Lucas vero domo Antiochenus, arte medicus, qui et cum Paulo diu conjunctissime vixit, et cum reliquis Apostolis studiose versatus est." Eusebius has a clearer statement in his "Quæstiones Evangelicæ", IV, i, 270: ho de Loukas to men genos apo tes Boomenes Antiocheias en--"Luke was by birth a native of the renowned Antioch" (Schmiedel, "Encyc. Bib."). Spitta, Schmiedel, and Harnack think this is a quotation from Julius Africanus (first half of the third century). In Codex Bezæ (D) Luke is introduced by a "we" as early as Acts 11:28; and, though this is not a correct reading, it represents a very ancient tradition. The writer of Acts took a special interest in Antioch and was well acquainted with it (Acts 11:19-27; 13:1; 14:18-21, 14:25, 15:22, 23, 30, 35; 18:22). We are told the locality of only one deacon, "Nicolas, a proselyte of Antioch", 6:5; and it has been pointed out by Plummer that, out of eight writers who describe the Russian campaign of 1812, only two, who were Scottish, mention that the Russian general, Barclay de Tolly, was of Scottish extraction. These considerations seem to exclude the conjecture of Renan and Ramsay that St. Luke was a native of Philippi.

St. Luke was not a Jew. He is separated by St. Paul from those of the circumcision (Colossians 4:14), and his style proves that he was a Greek. Hence he cannot be identified with Lucius the prophet of Acts 13:1, nor with Lucius of Romans 16:21, who was cognatus of St. Paul. From this and the prologue of the Gospel it follows that Epiphanius errs when he calls him one of the Seventy Disciples; nor was he the companion of Cleophas in the journey to Emmaus after the Resurrection (as stated by Theophylact and the Greek Menologium). St. Luke had a great knowledge of the Septuagint and of things Jewish, which he acquired either as a Jewish proselyte (St. Jerome) or after he became a Christian, through his close intercourse with the Apostles and disciples. Besides Greek, he had many opportunities of acquiring Aramaic in his native Antioch, the capital of Syria. He was a physician by profession, and St. Paul calls him "the most dear physician" (Colossians 4:14). This avocation implied a liberal education, and his medical training is evidenced by his choice of medical language. Plummer suggests that he may have studied medicine at the famous school of Tarsus, the rival of Alexandria and Athens, and possibly met St. Paul there. From his intimate knowledge of the eastern Mediterranean, it has been conjectured that he had lengthened experience as a doctor on board ship. He travailed a good deal, and sends greetings to the Colossians, which seems to indicate that he had visited them.

St. Luke first appears in the Acts at Troas (16:8 sqq.), where he meets St. Paul, and, after the vision, crossed over with him to Europe as an Evangelist, landing at Neapolis and going on to Philippi, "being assured that God had called us to preach the Gospel to them" (note especially the transition into first person plural at verse 10). He was, therefore, already an Evangelist. He was present at the conversion of Lydia and her companions, and lodged in her house. He, together with St. Paul and his companions, was recognized by the pythonical spirit: "This same following Paul and us, cried out, saying: These men are the servants of the most high God, who preach unto you the way of salvation" (verse 17). He beheld Paul and Silas arrested, dragged before the Roman magistrates, charged with disturbing the city, "being Jews", beaten with rods and thrown into prison. Luke and Timothy escaped, probably because they did not look like Jews (Timothy's father was a gentile). When Paul departed from Philippi, Luke was left behind, in all probability to carry on the work of Evangelist. At Thessalonica the Apostle received highly appreciated pecuniary aid from Philippi (Philippians 4:15-16), doubtless through the good offices of St. Luke. It is not unlikely that the latter remained at Philippi all the time that St. Paul was preaching at Athens and Corinth, and while he was travelling to Jerusalem and back to Ephesus, and during the three years that the Apostle was engaged at Ephesus. When St. Paul revisited Macedonia, he again met St. Luke at Philippi, and there wrote his Second Epistle to the Corinthians.

St. Jerome thinks it is most likely that St. Luke is "the brother, whose praise is in the gospel through all the churches" (2 Corinthians 8:18), and that he was one of the bearers of the letter to Corinth. Shortly afterwards, when St. Paul returned from Greece, St. Luke accompanied him from Philippi to Troas, and with him made the long coasting voyage described in Acts 20. He went up to Jerusalem, was present at the uproar, saw the attack on the Apostle, and heard him speaking "in the Hebrew tongue" from the steps outside the fortress Antonia to the silenced crowd. Then he witnessed the infuriated Jews, in their impotent rage, rending their garments, yelling, and flinging dust into the air. We may be sure that he was a constant visitor to St. Paul during the two years of the latter's imprisonment at Cæarea. In that period he might well become acquainted with the circumstances of the death of Herod Agrippa I, who had died there eaten up by worms" (skolekobrotos), and he was likely to be better informed on the subject than Josephus. Ample opportunities were given him, "having diligently attained to all things from the beginning", concerning the Gospel and early Acts, to write in order what had been delivered by those "who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word" (Luke 1:2, 3). It is held by many writers that the Gospel was written during this time, Ramsay is of opinion that the Epistle to the Hebrews was then composed, and that St. Luke had a considerable share in it. When Paul appealed to Cæsar, Luke and Aristarchus accompanied him from Cæsarea, and were with him during the stormy voyage from Crete to Malta. Thence they went on to Rome, where, during the two years that St. Paul was kept in prison, St. Luke was frequently at his side, though not continuously, as he is not mentioned in the greetings of the Epistle to the Philippians (Lightfoot, "Phil.", 35). He was present when the Epistles to the Colossians, Ephesians and Philemon were written, and is mentioned in the salutations given in two of them: "Luke the most dear physician, saluteth you" (Colossians 4:14); "There salute thee . . . Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke my fellow labourers" (Philem., 24). St. Jerome holds that it was during these two years Acts was written.

We have no information about St. Luke during the interval between St. Paul's two Roman imprisonments, but he must have met several of the Apostles and disciples during his various journeys. He stood beside St. Paul in his last imprisonment; for the Apostle, writing for the last time to Timothy, says: "I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course. . . . Make haste to come to me quickly. For Demas hath left me, loving this world. . . . Only Luke is with me" (2 Timothy 4:7-11). It is worthy of note that, in the three places where he is mentioned in the Epistles (Colossians 4:14; Philemon 24; 2 Timothy 4:11) he is named with St. Mark (cf. Colossians 4:10), the other Evangelist who was not an Apostle (Plummer), and it is clear from his Gospel that he was well acquainted with the Gospel according to St. Mark; and in the Acts he knows all the details of St. Peter's delivery—what happened at the house of St. Mark's mother, and the name of the girl who ran to the outer door when St. Peter knocked. He must have frequently met St. Peter, and may have assisted him to draw up his First Epistle in Greek, which affords many reminiscences of Luke's style. After St. Paul's martyrdom practically all that is known about him is contained in the ancient "Prefatio vel Argumentum Lucæ", dating back to Julius Africanus, who was born about A.D. 165. This states that he was unmarried, that he wrote the Gospel, in Achaia, and that he died at the age of seventy-four in Bithynia (probably a copyist's error for Bœotia), filled with the Holy Ghost. Epiphanius has it that he preached in Dalmatia (where there is a tradition to that effect), Gallia (Galatia?), Italy, and Macedonia. As an Evangelist, he must have suffered much for the Faith, but it is controverted whether he actually died a martyr's death. St. Jerome writes of him (De Vir. III., vii). "Sepultus est Constantinopoli, ad quam urbem vigesimo Constantii anno, ossa ejus cum reliquiis Andreæ Apostoli translata sunt [de Achaia?]."

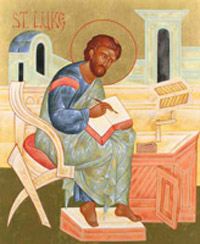

St. Luke its always represented by the calf or ox, the sacrificial animal, because his Gospel begins with the account of Zachary, the priest, the father of John the Baptist. He is called a painter by Nicephorus Callistus (fourteenth century), and by the Menology of Basil II, A.D. 980. A picture of the Virgin in S. Maria Maggiore, Rome, is ascribed to him, and can be traced to A.D. 847 It is probably a copy of that mentioned by Theodore Lector, in the sixth century. This writer states that the Empress Eudoxia found a picture of the Mother of God at Jerusalem, which she sent to Constantinople (see "Acta SS.", 18 Oct.). As Plummer observes. it is certain that St. Luke was an artist, at least to the extent that his graphic descriptions of the Annunciation, Visitation, Nativity, Shepherds. Presentation, the Shepherd and lost sheep, etc., have become the inspiring and favourite themes of Christian painters.

St. Luke is one of the most extensive writers of the New Testament. His Gospel is considerably longer than St. Matthew's, his two books are about as long as St. Paul's fourteen Epistles: and Acts exceeds in length the Seven Catholic Epistles and the Apocalypse. The style of the Gospel is superior to any N.T. writing except Hebrews. Renan says (Les Evangiles, xiii) that it is the most literary of the Gospels. St. Luke is a painter in words. "The author of the Third Gospel and of the Acts is the most versatile of all New Testament writers. He can be as Hebraistic as the Septuagint, and as free from Hebraisms as Plutarch. . . He is Hebraistic in describing Hebrew society and Greek when describing Greek society" (Plummer, introd.). His great command of Greek is shown by the richness of his vocabulary and the freedom of his constructions. Authenticity of the Gospel Internal evidence

The internal evidence may be briefly summarized as follows:

* The author of Acts was a companion of Saint Paul, namely, Saint Luke; and * the author of Acts was the author of the Gospel.

The arguments are given at length by Plummer, "St. Luke" in "Int. Crit. Com." (4th ed., Edinburgh, 1901); Harnack, "Luke the Physician" (London, 1907); "The Acts of the Apostles" (London, 1909); etc.

(1) The Author of Acts was a companion of Saint Paul, namely, Saint Luke

There is nothing more certain in Biblical criticism than this proposition. The writer of the "we" sections claims to be a companion of St. Paul. The "we" begins at Acts 16:10, and continues to 16:17 (the action is at Philippi). It reappears at 20:5 (Philippi), and continues to 21:18 (Jerusalem). It reappears again at the departure for Rome, 27:1 (Greek text), and continues to the end of the book.

Plummer argues that these sections are by the same author as the rest of the Acts:

* from the natural way in which they fit in; * from references to them in other parts; and * from the identity of style.

The change of person seems natural and true to the narrative, but there is no change of language. The characteristic expressions of the writer run through the whole book, and are as frequent in the "we" as in the other sections. There is no change of style perceptible. Harnack (Luke the Physician, 40) makes an exhaustiveexamination of every word and phrase in the first of the "we" sections (xvi, 10-17), and shows how frequent they are in the rest of the Acts and the Gospel, when compared with the other Gospels. His manner of dealing with the first word ( hos) will indicate his method: "This temporal hos is never found in St. Matthew and St. Mark, but it occurs forty-eight times in St. Luke (Gospels and Acts), and that in all parts of the work." When he comes to the end of his study of this section he is able to write: "After this demonstration those who declare that this passage was derived from a source, and so was not composed by the author of the whole work, take up a most difficult position. What may we suppose the author to have left unaltered in the source? Only the 'we'. For, in fact, nothing else remains. In regard to vocabulary, syntax, and style, he must have transformed everything else into his own language. As such a procedure is absolutely unimaginable, we are simply left to infer that the author is here himself speaking." He even thinks it improbable, on account of the uniformity of style, that the author was copying from a diary of his own, made at an earlier period. After this, Harnack proceeds to deal with the remaining "we" sections, with like results. But it is not alone in vocabulary, syntax and style, that this uniformity is manifest. In "The Acts of the Apostles", Harnack devotes many pages to a detailed consideration of the manner in whichchronological data, and terms dealing with lands, nations, cities, and houses, are employed throughout the Acts, as well as the mode of dealing with persons and miracles, and he everywhere shows that the unity of authorship cannot be denied except by those who ignore the facts. This same conclusion is corroborated by the recurrence of medical language in all parts of the Acts and the Gospel.

That the companion of St. Paul who wrote the Acts was St. Luke is the unanimous voice of antiquity. His choice of medical language proves that the author was a physician. Westein, in his preface to the Gospel ("Novum Test. Græcum", Amsterdam, 1741, 643), states that there are clear indications of his medical profession throughout St. Luke's writings; and in the course of his commentary he points out several technical expressions common to the Evangelist and the medical writings of Galen. These were brought together by the Bollandists ("Acta SS.", 18 Oct.). In the "Gentleman's Magazine" for June, 1841, a paper appeared on the medical language of St. Luke. To the instances given in that article, Plummer and Harnack add several others; but the great book on the subject isHobart "The Medical Language of St. Luke" (Dublin, 1882). Hobart works right through the Gospel and Acts and points out numerous words and phrases identical with those employed by such medical writers as Hippocrates, Arctæus, Galen, and Dioscorides. A few are found in Aristotle, but he was a doctor's son. The words and phrases cited are either peculiar to the Third Gospel and Acts, or are more frequent than in other New Testament writings. The argument is cumulative, and does not give way with its weakest strands. When doubtful cases and expressions common to the Septuagint, are set aside, a large number remain that seem quite unassailable. Harnack (Luke the Physician! 13) says: "It is as good as certain from the subject-matter, and more especially from the style, of this great work that the author was a physician by profession. Of course, in making such a statement one still exposes oneself to the scorn of thecritics, and yet the arguments which are alleged in its support are simply convincing. . . . Those, however, who have studied it [Hobart's book] carefully, will, I think, find it impossible to escape the conclusion that the question here is not one of merely accidental linguistic coloring, but that this great historical work was composed by a writer who was either a physician or was quite intimately acquainted with medical language and science. And, indeed, this conclusion holds good not only for the 'we' sections, but for the whole book." Harnack gives the subject special treatment in an appendix of twenty-two pages.Hawkins and Zahn come to the same conclusion. The latter observes (Einl., II, 427): "Hobart has proved for everyone who can appreciate proof that the author of the Lucan work was a man practised in the scientific language of Greek medicine--in short, a Greek physician" (quoted by Harnack, op. cit.).

In this connection, Plummer, though he speaks more cautiously of Hobart's argument, is practically in agreement with these writers. He says that when Hobart's list has been well sifted a considerable number of words remains. "The argument", he goes on to say "is cumulative. Any two or three instances of coincidence withmedical writers may be explained as mere coincidences; but the large number of coincidences renders their explanation unsatisfactory for all of them, especially where the word is either rare in the LXX, or not found there at all" (64). In "The Expositor" (Nov. 1909, 385 sqq.), Mayor says of Harnack's two above-cited works: "He has in opposition to the Tübingen school of critics, successfully vindicated for St. Luke the authorship of the two canonical books ascribed to him, and has further proved that, with some few omissions, they may be accepted as trustworthy documents. . . . I am glad to see that the English translator . . . has now been converted by Harnack's argument, founded in part, as he himself confesses, on the researches of English scholars, especially Dr. Hobart, Sir W. M. Ramsay, and Sir John Hawkins." There is a striking resemblance between the prologue of the Gospel and a preface written by Dioscorides, a medical writer who studied at Tarsus in the first century (see Blass, "Philology of the Gospels"). The words with which Hippocrates begins his treatise "On Ancient Medicine" should be noted in this connection: 'Okosoi epecheiresan peri iatrikes legein he graphein, K. T. L. (Plummer, 4). When all these considerations are fully taken into account, they prove that the companion of St. Paul who wrote the Acts (and the Gospel) was a physician. Now, we learn from St. Paul that he had such a companion. Writing to the Colossians (iv, 11), he says: "Luke, the most dear physician, saluteth you." He was, therefore, with St. Paul when he wrote to the Colossians, Philemon, and Ephesians; and also when he wrote the Second Epistle to Timothy. From the manner in which he is spoken of, a long period of intercourse is implied.

(2) The Author of Acts was the Author of the Gospel

"This position", says Plummer, "is so generally admitted by critics of all schools that not much time need be spent in discussing it." Harnack may be said to be the latest prominent convert to this view, to which he gives elaborate support in the two books above mentioned. He claims to have shown that the earlier critics went hopelessly astray, and that the traditional view is the right one. This opinion is fast gaining ground even amongst ultra critics, and Harnack declares that the others hold out because there exists a disposition amongst them to ignore the facts that tell against them, and he speaks of "the truly pitifulhistory of the criticism of the Acts". Only the briefest summary of the arguments can be given here. The Gospel and Acts are both dedicated to Theophilus and the author of the latter work claims to be the author of the former ( Acts 1:1). The style and arrangement of both are so much alike that the supposition that one was written by a forger in imitation of the other is absolutely excluded. The required power of literary analysis was then unknown, and, if it were possible, we know of no writer of that age who had the wonderful skill necessary to produce such an imitation. It is to postulate a literary miracle, says Plummer, to suppose that one of the books was a forgery written in Imitation of the other. Such an idea would not have occurred to anyone; and, if it had, he could not have carried it out with such marvellous success. If we take a fewchapters of the Gospel and note down the special, peculiar, and characteristic words, phrases and constructions, and then open the Acts at random, we shall find the same literary peculiarities constantly recurring. Or, if we begin with the Acts, and proceed conversely, the same results will follow. In addition to similarity, there are parallels of description, arrangement, and points of view, and the recurrence of medical language, in both books, has been mentioned under the previous heading.

We should naturally expect that the long intercourse between St. Paul and St. Luke would mutually influence their vocabulary, and their writings show that this was really the case. Hawkins (Horæ Synopticæ) and Bebb (Hast., "Dict. of the Bible", s.v. "Luke, Gospel of") state that there are 32 words found only in St. Matt. and St. Paul; 22 in St. Mark and St. Paul; 21 in St. John and St. Paul; while there are 101 found only in St. Luke and St. Paul. Of the characteristic words and phrases which mark the three Synoptic Gospels a little more than half are common to St. Matt. and St. Paul, less than half to St. Mark and St. Paul and two-thirds to St. Luke and St. Paul. Several writers have given examples of parallelism between the Gospel and the Pauline Epistles. Among the most striking are those given by Plummer (44). The same author gives long lists of words and expressions found in theGospel and Acts and in St. Paul, and nowhere else in the New Testament. But more than this, Eager in "The Expositor" (July and August, 1894), in his attempt to prove that St. Luke was the author of Hebrews, has drawn attention to the remarkable fact that the Lucan influence on the language of St. Paul is much more marked in those Epistles where we know that St. Luke was his constant companion. Summing up, he observes: "There is in fact sufficient ground for believing that these books. Colossians, II Corinthians, the Pastoral Epistles, First (and to a lesser extent Second) Peter, possess a Lucan character." When all these points are taken into consideration, they afford convincing proof that the author of the Gospel and Acts was St. Luke, the beloved physician, the companion of St. Paul, and this is fully borne out by the external evidence. External evidence

The proof in favour of the unity of authorship, derived from the internal character of the two books, is strengthened when taken in connection with the external evidence. Every ancient testimony for the authenticity of Acts tells equally in favour of the Gospel; and every passage for the Lucan authorship of the Gospel gives a like support to the authenticity of Acts. Besides, in many places of the early Fathers both books are ascribed to St. Luke. The external evidence can be touched upon here only in the briefest manner. For external evidence in favour of Acts, see ACTS OF THE APOSTLES.

The many passages in St. Jerome, Eusebius, and Origen, ascribing the books to St. Luke, are important not only as testifying to the belief of their own, but also of earlier times. St. Jerome and Origen were great travellers, and all three were omnivorous readers. They had access to practically the whole Christian literature of preceding centuries; but they nowhere hint that the authorship of the Gospel (and Acts) was ever called in question. This, taken by itself, would be a stronger argument than can be adduced for the majority of classical works. But we have much earlier testimony. Clement of Alexandria was probably born at Athens about A.D. 150. He travelled much and had for instructors in the Faith an Ionian, an Italian, a Syrian, an Egyptian, an Assyrian, and a Hebrew in Palestine. "And these men, preserving the true tradition of the blessed teaching directly from Peter and James, John and Paul, the holy Apostles, son receiving it from father, came by God's providence even unto us, to deposit among us those seeds [of truth] which were derived from their ancestors and the Apostles". (Stromata I.1.11; cf. Euseb., Church History V.11). He holds that St. Luke's Gospel was written before that of St. Mark, and he uses the four Gospels just as any modern Catholic writer. Tertullian was born at Carthage, lived some time in Rome, and then returned to Carthage. His quotations from the Gospels, when brought together by Rönsch, cover two hundred pages. He attacks Marcion for mutilating St. Luke's Gospel. and writes: "I say then that among them, and not only among the Apostolic Churches, but among all the Churches which are united with them in Christian fellowship, the Gospel of Luke, which we earnestly defend, has been maintained from its first publication" (Adv. Marc., IV, v).

The testimony of St. Irenæus is of special importance. He was born in Asia Minor, where he heard St. Polycarp give his reminiscences of St. John the Apostle, and in his numerous writings he frequently mentions other disciples of the Apostles. He was priest in Lyons during the persecution in 177, and was the bearer of the letter of the confessors to Rome. His bishop, Pothinus, whom be succeeded, was ninety years of age when he gained the crown of martyrdom in 177, and must have been born while some of the Apostles and very many of their hearers were still living. St. Irenæus, who was born about A.D. 130 (some say much earlier), is, therefore, a witness for the early tradition of Asia Minor, Rome, and Gaul. He quotes the Gospels just as any modern bishop would do, he calls them Scripture, believes even in their verbal inspiration; shows how congruous it is that there are four and only four Gospels; and says that Luke, who begins with the priesthood and sacrifice of Zachary, is the calf. When we compare his quotations with those of Clement of Alexandria, variant readings of text present themselves. There was already established an Alexandrian type of text different from that used in the West. The Gospels had been copied and recopied so often, that, through errors of copying, etc., distinct families of text had time to establish themselves. The Gospels were so widespread that they became known to pagans. Celsus in his attack on the Christian religion was acquainted with the genealogy in St. Luke's Gospel, and his quotations show the same phenomena of variant readings.

The next witness, St. Justin Martyr, shows the position of honour the Gospels held in the Church, in the early portion of the century. Justin was born in Palestine about A.D. 105, and converted in 132-135. In his "Apology" he speaks of the memoirs of the Lord which are called Gospels, and which were written by Apostles (Matthew, John) and disciples of the Apostles (Mark, Luke). In connection with the disciples of the Apostles he cites the verses of St. Luke on the Sweat of Blood, and he has numerous quotations from all four. Westcott shows that there is no trace in Justin of the use of any written document on the life of Christ except our Gospels. "He [Justin] tells us that Christ was descended from Abraham through Jacob, Judah, Phares, Jesse, David--that the Angel Gabriel was sent to announce His birth to the Virgin Mary—that it was in fulfillment of the prophecy of Isaiah . . . that His parents went thither [to Bethlehem] in consequence of an enrolment under Cyrinius--that as they could not find a lodging in the village they lodged in a cave close by it, whereChrist was born, and laid by Mary in a manger", etc. (Westcott, "Canon", 104). There is a constant intermixture in Justin's quotations of the narratives of St. Matthew and St. Luke. As usual in apologetical works, such as the apologies of Tatian, Athenagoras, Theophilus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Cyprian, and Eusebius, he does not name his sources because he was addressing outsiders. He states, however, that the memoirs which were called Gospels were read in the churches on Sunday along with the writings of the Prophets, in other words, they were placed on an equal rank with the Old Testament. In the "Dialogue", cv, we have a passage peculiar to St. Luke. "Jesus as He gave up His Spirit upon the Cross said, Father, into thy hands I commend my Spirit?' [Luke, xxiii. 46], even as I learned from the Memoirs of this fact also." These Gospels which were read every Sunday must be the same as our four, which soon after, in the time of Irenæus, were in such long established honour, and regarded by him as inspired by the Holy Ghost. We never hear, says Salmon, of any revolution dethroning one set of Gospels and replacing them by another; so we may be sure that the Gospels honoured by the Church in Justin's day were the same as those to which the same respect was paid in the days of Irenæus, not many years after. This conclusion is strengthened not only by the nature of Justin's quotations, but by the evidence afforded by his pupil Tatian, the Assyrian, who lived a long time with him in Rome, and afterwards compiled his harmony of the Gospels, his famous "Diatessaron", in Syriac, from our four Gospels. He had travelled a great deal, and the fact that he uses only those shows that they alone were recognized by St. Justin and the Catholic Church between 130-150. This takes us back to the time when many of the hearers of the Apostles and Evangelists were still alive; for it is held by many scholars that St. Luke lived till towards the end of the first century.

Irenæus, Clement, Tatian, Justin, etc., were in as good a position for forming a judgment on the authenticity of the Gospels as we are of knowing who were the authors of Scott's novels, Macaulay's essays, Dickens's early novels, Longfellow's poems, no. xc of "Tracts for the Times" etc. But the argument does not end here. Many of the heretics who flourished from the beginning of the second century till A.D. 150 admitted St. Luke's Gospel as authoritative. This proves that it had acquired an unassailable position long before these heretics broke away from the Church. The Apocryphal Gospel of Peter, about A.D. 150, makes use of our Gospels. About the same time the Gospels, together with their titles, were translated into Latin; and here, again, we meet the phenomena of variant readings, to be found in Clement, Irenæus, Old Syriac, Justin, and Celsus, pointing to a long period of previous copying. Finally, we may ask, if the author of the two books were not St. Luke, who was he?

Harnack (Luke the Physician, 2) holds that as the Gospel begins with a prologue addressed to an individual (Theophilus) it must, of necessity, have contained in its title the name of its author. How can we explain, if St. Luke were not the author, that the name of the real, and truly great, writer came to be completelyburied in oblivion, to make room for the name of such a comparatively obscure disciple as St. Luke? Apart from his connection, as supposed author, with the Third Gospel and Acts, was no more prominent than Aristarchus and Epaphras; and he is mentioned only in three places in the whole of the New Testament. If a false name were substituted for the true author, some more prominent individual would have been selected. Integrity of the Gospel

Marcion rejected the first two chapters and some shorter passages of the gospel, and it was at one time maintained by rationalistic writers that his was the original Gospel of which ours is a later expansion. This is now universally rejected by scholars. St. Irenæus, Tertullian, and Epiphanius charged him with mutilating the Gospel; and it is known that the reasons for his rejection of those portions were doctrinal. He cut out the account of the infancy and the genealogy, because he denied the human birth of Christ. As he rejected the Old Testament all reference to it had to be excluded. That the parts rejected by Marcion belong to the Gospel is clear from their unity of style with the remainder of the book. The characteristics of St. Luke's style run through the whole work, but are more frequent in the first twochapters than anywhere else; and they are present in the other portions omitted by Marcion. No writer in those days was capable of successfully forging such additions. The first two chapters, etc., are contained in all the manuscripts and versions, and were known to Justin Martyr and other competent witnesses. On the authenticity of the verses on the Bloody Sweat, see AGONY OF CHRIST. Purpose and contents

The Gospel was written, as is gathered from the prologue (i, 1-4), for the purpose of giving Theophilus (and others like him) increased confidence in the unshakable firmness of the Christian truths in which he had been instructed, or "catechized"--the latter word being used, according to Harnack, in its technical sense. TheGospel naturally falls into four divisions:

* Gospel of the infancy, roughly covered by the Joyful Mysteries of the Rosary (ch. i, ii); * ministry in Galilee, from the preaching of John the Baptist (iii, 1, to ix, 50); * journeyings towards Jerusalem (ix, 51-xix, 27); * Holy Week: preaching in and near Jerusalem, Passion, and Resurrection (xix, 28, to end of xxiv).

We owe a great deal to the industry of St. Luke. Out of twenty miracles which he records six are not found in the other Gospels: draught of fishes, widow of Naim's son, man with dropsy, ten lepers, Malchus's ear, spirit of infirmity. He alone has the following eighteen parables: good Samaritan, friend at midnight, rich fool, servants watching, two debtors, barren fig-tree, chief seats, great supper, rash builder, rash king, lost groat, prodigal son, unjust steward, rich man and Lazarus, unprofitable servants, unjust judge, Pharisee and publican, pounds. The account of the journeys towards Jerusalem (ix, 51-xix, 27) is found only in St. Luke; and he gives special prominence to the duty of prayer. Sources of the Gospel; synoptic problem

The best information as to his sources is given by St. Luke, in the beginning of his Gospel. As many had written accounts as they heard them from "eyewitnesses and ministers of the word", it seemed good to him also, having diligently attained to all things from the beginning, to write an ordered narrative. He had two sources of information, then, eyewitnesses (includingApostles ) and written documents taken down from the words of eyewitnesses. The accuracy of these documents he was in a position to test by his knowledge of the character of the writers, and by comparing them with the actual words of the Apostles and other eyewitnesses.

That he used written documents seems evident on comparing his Gospel with the other two Synoptic Gospels, Matthew and Mark. All three frequently agree even in minute details, but in other respects there is often a remarkable divergence, and to explain these phenomena is theSynoptic Problem. St. Matthew and St. Luke alone give an account of the infancy of Christ, both accounts are independent. But when they begin the public preaching they describe it in the same way, here agreeing with St. Mark. When St. Mark ends, the two others again diverge. They agree in the main both in matter and arrangement within the limits covered by St. Mark, whose order they generally follow. Frequently all agree in the order of the narrative, but, where two agree, Mark and Luke agree against the order of Matthew, or Mark and Matthew agree against the order of Luke; Mark is always in the majority, and it is not proved that the other two ever agree against the order followed by him. Within the limits of the ground covered by St. Mark, the two other Gospels have several sections in common not found in St. Mark, consisting for the most part of discourses, and there is a closer resemblance between them than between any two Gospels where the three go over the same ground. The whole of St. Mark is practically contained in the other two. St. Matthew and St. Luke have large sections peculiar to themselves, such as the different accounts of the infancy, and the journeys towards Jerusalem in St. Luke. The parallel records have remarkable verbal coincidences. Sometimes the Greek phrases are identical, sometimes but slightly different, and again more divergent. There are various theories to explain the fact of thematter and language common to the Evangelists. Some hold that it is due to the oral teaching of the Apostles, which soon became stereotyped from constant repetition. Others hold that it is due to written sources, taken down from such teaching. Others, again, strongly maintain thatMatthew and Luke used Mark or a written source extremely like it. In that case, we have evidence how very closely they kept to the original. The agreement between the discourses given by St. Luke andSt. Matthew is accounted for, by some authors, by saying that both embodied the discourses of Christ that had been collected and originally written in Aramaic by St. Matthew. The long narratives of St. Luke not found in these two documents are, it is said, accounted for by his employment of what he knew to be other reliable sources, either oral or written. (The question is concisely but clearly stated by Peake "A Critical Introduction to the New Testament", London, 1909, 101. Several other works on the subject are given in the literature at the end of this article.) Saint Luke's accuracy

Very few writers have ever had their accuracy put to such a severe test as St. Luke, on account of the wide field covered by his writings, and the consequent liability (humanly speaking) of making mistakes; and on account of the fierce attacks to which he has been subjected.

It was the fashion, during the nineteenth century, with German rationalists and their imitators, to ridicule the "blunders" of Luke, but that is all being rapidly changed by the recent progress of archæological research. Harnack does not hesitate to say that these attacks were shameful, and calculated to bring discredit, not on the Evangelist, but upon his critics, and Ramsay is but voicing the opinion of the best modern scholars when he calls St. Luke a great and accurate historian. Very few have done so much as this latter writer, in his numerous works and in his articles in "The Expositor", to vindicate the extreme accuracy of St. Luke. Whereverarchæology has afforded the means of testing St. Luke's statements, they have been found to be correct; and this gives confidence that he is equally reliable where no such corroboration is as yet available. For some of the details see ACTS OF THE APOSTLES, where a very full bibliography is given.

For the sake of illustration, one or two examples may here be given:

(1) Sergius Paulus, Proconsul in Cyprus

St. Luke says (Acts 13) that when St. Paul visited Cyprus (in the reign of Claudius) Sergius Paulus was proconsul (anthupatos) there. Grotius asserted that this was an abuse of language, on the part of the natives, who wished to flatter the governor by calling him proconsul, instead of proprætor (antistrategos), which he really was; and that St. Luke used the popular appellation. Even Baronius (Annales, ad Ann. 46) supposed that, though Cyprus was only a prætorian province, it was honoured by being ruled by the proconsul of Cilicia, who must have been Sergius Paulus. But this is all a mistake. Cato captured Cyprus, Cicero was proconsul of Cilicia and Cyprus in 52 B.C.; Mark Antony gave the island to Cleopatra; Augustus made it a prætorian province in 27 B.C., but in 22 B.C. he transferred it to the senate, and it became again a proconsular province. This latter fact is not stated by Strabo, but it is mentioned by Dion Cassius (LIII). In Hadrian's time it was once more under a proprætor, while under Severus it was again administered by a proconsul. There can be no doubt that in the reign of Claudius, when St. Paul visited it, Cyprus was under a proconsul (anthupatos), as stated by St. Luke. Numerous coins have been discovered in Cyprus, bearing the head and name of Claudius on one side, and the names of the proconsuls of Cyprus on the other. A woodcut engraving of one is given in Conybeare and Howson's "St. Paul", at the end of chapter v. On the reverse it has: EPI KOMINOU PROKAU ANTHUPATOU: KUPRION--"Money of the Cyprians under Cominius Proclus, Proconsul." The head of Claudius (with his name) is figured on the other side. General Cesnola discovered a long inscription on a pedestal of white marble, at Solvi, in the north of the island, having the words: EPI PAULOU ANTHUPATOU--"Under Paulus Proconsul." Lightfoot, Zochler, Ramsay, Knabenbauer, Zahn, and Vigouroux hold that this was the actual (Sergius) Paulus of Acts 13:7.

(2) The Politarchs in Thessalonica

An excellent example of St. Luke's accuracy is afforded by his statement that rulers of Thessalonica were called "politarchs" (politarchai--Acts 17:6, 8). The word is not found in the Greek classics; but there is a large stone in the British Museum, which was found in an arch in Thessalonica, containing an inscription which is supposed to date from the time of Vespasian. Here we find the word used by St. Luke together with the names of several such politarchs, among them being names identical with some of St. Paul's converts: Sopater, Gaius, Secundus. Burton in "American Journal of Theology" (July, 1898) has drawn attention to seventeen inscriptions proving the existence of politarchs in ancient times. Thirteen were found in Macedonia, and five were discovered in Thessalonica, dating from the middle of the first to the end of the second century.

(3) Knowledge of Pisidian Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe

The geographical, municipal, and political knowledge of St. Luke, when speaking of Pisidian Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, and Derbe, is fully borne out by recent research (see Ramsay, "St. Paul the Traveller", and other references given in EPISTLE TO THE GALATIANS).

(4) Knowledge of Philippian customs

He is equally sure when speaking of Philippi, a Roman colony, where the duumviri were called "prætors" (strategoi--Acts 16:20, 35), a lofty title which duumviri assumed in Capua and elsewhere, as we learn from Cicero and Horace (Sat., I, v, 34). They also had lictors (rabsouchoi), after the manner of real prætors.

(5) References to Ephesus, Athens, and Corinth

His references to Ephesus, Athens, Corinth, are altogether in keeping with everything that is now known of these cities. Take a single instance: "In Ephesus St. Paul taught in the school of Tyrannus, in the city of Socrates he discussed moral questions in the market-place. How incongruous it would seem if the methods were transposed! But the narrative never makes a false step amid all the many details as the scene changes from city to city; and that is the conclusive proof that it is a picture of real life" (Ramsay, op. cit., 238). St. Luke mentions (Acts 18:2) that when St. Paul was at Corinth the Jews had been recently expelled from Rome by Claudius, and this is confirmed by a chance statement of Suetonius. He tells us (ibid., 12) that Gallio was then proconsul in Corinth (the capital of the Roman province of Achaia). There is no direct evidence that he was proconsul in Achaia, but his brother Seneca writes that Gallio caught a fever there, and went on a voyage for his health. The description of the riot at Ephesus (Acts 19) brings together, in the space of eighteen verses, an extraordinary amount of knowledge of the city, that is fully corroborated by numerous inscriptions, and representations on coins, medals, etc., recently discovered. There are allusions to the temple of Diana (one of the seven wonders of the world), to the fact that Ephesus gloried in being her temple-sweeper her caretaker (neokoros), to the theatre as the place of assembly for the people, to the town clerk (grammateus), to the Asiarchs, to sacrilegious (ierosuloi), to proconsular sessions, artificers, etc. The ecclesia (the usual word in Ephesus for the assembly of the people) and the grammateus or town-clerk (the title of a high official frequent on Ephesian coins) completely puzzled Cornelius a Lapide, Baronius, and other commentators, who imagined the ecclesia meant a synagogue, etc. (see Vigouroux, "Le Nouveau Testament et les Découvertes Archéologiques", Paris, 1890).

(6) The Shipwreck

The account of the voyage and shipwreck described in Acts (27 and 28) is regarded by competent authorities on nautical matters as a marvellous instance of accurate description (see Smith's classical work on the subject, "Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul" (4th ed., London, 1880). Blass (Acta Apostolorum, 186) says: "Extrema duo capita habent descriptionem clarissimam itineris maritimi quod Paulus in Italiam fecit: quæ descriptio ab homine harum rerum perito judicata est monumentum omnium pretiosissimum, quæ rei navalis ex tote antiquitate nobis relicta est. V. Breusing, 'Die Nautik der Alten' (Bremen, 1886)." See also Knowling "The Acts of the Apostles" in "Exp. Gr. Test." (London, 1900). Lysanias tetrarch of Abilene

Gfrörer, B. Bauer, Hilgenfeld, Keim, and Holtzmann assert that St. Luke perpetrated a gross chronological blunder of sixty years by making Lysanias, the son of Ptolemy, who lived 36 B.C., and was put to death by Mark Antony, tetrarch of Abilene when John the Baptist began to preach (iii, 1). Strauss says: "He [Luke] makes rule, 30 years after the birth of Christ, a certain Lysanias, who had certainly been slain 30 years previous to that birth--a slight error of 60 years." On the face of it, it is highly improbable that such a careful writer as St. Luke would have gone out of his way to run the risk of making such a blunder, for the mere purpose of helping to fix the date of the public ministry. Fortunately, we have a complete refutation supplied by Schürer, a writer by no means over friendly to St. Luke, as we shall see when treating of theCensus of Quirinius. Ptolemy Mennæus was King of the Itureans (whose kingdom embraced the Lebanon and plain of Massyas with the capital Chalcis, between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon) from 85-40 B.C. His territories extended on the east towards Damascus, and on the south embraced Panias, and part, at least, of Galilee. Lysanias the older succeeded his father Ptolemy about 40 B.C. (Josephus, "Ant.", XIV, xii, 3; "Bell Jud.", I, xiii, 1), and is styled by Dion Cassius "King of the Itureans" (XLIX, 32). After reigning about four or five years he was put to death by Mark Antony, at the instigation of Cleopatra, who received a large portion of his territory (Josephus, "Ant.", XV, iv, 1; "Bel. Jud.", I, xxii, 3; Dion Cassius, op. cit.).

As the latter and Porphyry call him "king", it is doubtful whether the coins bearing the superscription "Lysanias tetrarch and high priest" belong to him, for there were one or more later princes called Lysanias. After his death his kingdom was gradually divided up into at least four districts, and the three principal ones were certainly not called after him. A certain Zenodorus took on lease the possessions of Lysanias, 23 B.C., but Trachonitis was soon taken from him and given to Herod. On the death of Zenodorus in 20 B.C., Ulatha and Panias, the territories over which he ruled, were given by Augustus to Herod. This is called the tetrarchy of Zenodorus by Dion Cassius. "It seems therefore that Zenodorus, after the death of Lysanias, had received on rent a portion of his territory from Cleopatra, and that after Cleopatra's death this 'rented' domain, subject to tribute, was continued to him with the title of tetrarch" (Schürer, I, II app., 333, i). Mention is made on a monument, atHeliopolis , of "Zenodorus, son of the tetrarch Lysanias". It has been generally supposed that this is the Zenodorus just mentioned, but it is uncertain whether the first Lysanias was ever called tetrarch. It is proved from the inscriptions that there was a genealogical connection between the families of Lysanias and Zenodorus, and the same name may have been often repeated in the family. Coins for 32, 30, and 25 B.C., belonging to our Zenodorus, have the superscription, "Zenodorus tetrarch and high priest.' After the death of Herod the Great a portion of the tetrarchy of Zenodorus went to Herod's son, Philip (Jos., "Ant.", XVII, xi, 4), referred to by St. Luke, "Philip being tetrarch of Iturea" (Luke 3:1).

Another tetrarchy sliced off from the dominions of Zenodorus lay to the east between Chalcis and Damascus, and went by the name of Abila or Abilene. Abila is frequently spoken of by Josephus as a tetrarchy, and in "Ant.", XVIII, vi, 10, he calls it the "tetrarchy of Lysanias". Claudius, in A.D. 41, conferred "Abila of Lysanias" on Agrippa I (Ant., XIX, v, 1). In a. D. 53, Agrippa II obtained Abila, "which last had been the tetrarchy of Lysanias" (Ant., XX., vii, 1). "From these passages we see that the tetrarchy of Abila had belonged previously to A.D. 37 to a certain Lysanias, and seeing that Josephus nowhere previously makes any mention of another Lysanias, except the contemporary of Anthony and Cleopatra, 40-36 B.C. . . . criticism has endeavoured in various ways to show that there had not afterwards been any other, and that the tetrarchy of Abilene had its name from the older Lysanias. But this is impossible" (Schürer, 337). Lysanias I inherited the Iturean empire of his father Ptolemy, of which Abila was but a small and very obscure portion. Calchis in Coele-Syria was the capital of his kingdom, not Abila in Abilene. He reigned only about four years and was a comparatively obscure individual when compared with his father Ptolemy, or his successor Zenodorus, both of whom reigned many years. There is no reason why any portion of his kingdom should have been called after his name rather than theirs, and it is highly improbable that Josephus speaks of Abilene as called after him seventy years after his death. As Lysanias I was king over the whole region, one small portion of it could not be called his tetrarchy or kingdom, as is done by Josephus (Bel. Jud., II, xii, 8). "It must therefore be assumed as certain that at a later date the district of Abilene had been severed from the kingdom of Calchis, and had been governed by a younger Lysanias as tetrarch" (Schürer, 337). The existence of such a late Lysanias is shown by an inscription found at Abila, containing the statement that a certain Nymphaios, the freedman of Lysanias, built a street and erected a temple in the time of the "August Emperors". Augusti (Sebastoi) in the plural was never used before the death of Augustus, A.D. 14. The first contemporary Sebastoi were Tiberius and his mother Livia, i.e. at a time fifty years after the first Lysanias. An inscription at Heliopolis, in the same region, makes it probable that there were several princes of this name. "The Evangelist Luke is thoroughly correct when he assumes (iii, 1) that in the fifteenth year of Tiberius there was a Lysanias tetrarch of Abilene" (Schürer, op. cit., where full literature is given; Vigouroux, op. cit.). Who spoke the Magnificat?

Lately an attempt has been made to ascribe the Magnificat to Elizabeth instead of to the Blessed Virgin. All the early Fathers, all the Greek manuscripts, all the versions, all the Latin manuscripts (except three) have the reading in Luke 1:46: Kai eipen Mariam--Et ait Maria [And Mary said]: Magnificat anima mea Dominum, etc. Three Old Latin manuscripts (the earliest dating from the end of the fourth cent.), a, b, l (called rhe by Westcott and Hort), have Et ait Elisabeth. These tend to such close agreement that their combined evidence is single rather than threefold. They are full of gross blunders and palpable corruptions, and the attempt to pit their evidence against the many thousands ofGreek, Latin, and other manuscripts, is anything but scientific. If the evidence were reversed, Catholics would be held up to ridicule if they ascribed the Magnificat to Mary. The three manuscripts gain little or no support from the internal evidence of the passage. The Magnificat is a cento from the song of Anna (1 Samuel 2), the Psalms, and other places of the Old Testament. If it were spoken by Elizabeth it is remarkable that the portion of Anna's song that was most applicable to her is omitted: "The barren hath borne many: and she that had many children is weakened." See, on this subject, Emmet in "The Expositor" (Dec., 1909); Bernard, ibid. (March, 1907); and the exhaustive works of two Catholic writers: Ladeuze, "Revue d'histoire ecclésiastique" (Louvain, Oct., 1903); Bardenhewer, "Maria Verkündigung" (Freiburg, 1905). The census of Quirinius

No portion of the New Testament has been so fiercely attacked as Luke 2:1-5. Schürer has brought together, under six heads, a formidable array of all the objections that can he urged against it. There is not space to refute them here; but Ramsay in his "WasChrist born in Bethlehem?" has shown that they all fall to the ground:--

(1) St. Luke does not assert that a census took place all over the Roman Empire before the death of Herod, but that a decision emanated from Augustus that regular census were to be made. Whether they were carried out in general, or not, was no concern of St. Luke's. If history does not prove the existence of such a decree it certainly proves nothing against it. It was thought for a long time that the system of Indictions was inaugurated under the early Roman emperors, it is now known that they owe their origin to Constantine the Great (the first taking place fifteen years after his victory of 312), and this in spite of the fact that history knew nothing of the matter. Kenyon holds that it is very probable that Pope Damasus ordered the Vulgate to be regarded as the only authoritative edition of the Latin Bible; but it would be difficult to Prove it historically. If "history knows nothing" of the census in Palestine before 4 B.C. neither did it know anything of the fact that under the Romans in Egypt regular personal census were held every fourteen years, at least from A.D. 20 till the time of Constantine. Many of these census papers have been discovered, and they were called apographai, the name used by St. Luke. They were made without any reference to property or taxation. The head of the household gave his name and age, the name and age of his wife, children, and slaves. He mentioned how many were included in the previous census, and how many born since that time. Valuation returns were made every year. The fourteen years' cycle did not originate in Egypt (they had a different system before 19 B.C.), but most probably owed its origin to Augustus, 8 B.C., the fourteenth year of his tribunitia potestas, which was a great year in Rome, and is called the year I in some inscriptions. Apart from St. Luke and Josephus, history is equally ignorant of the second enrolling in Palestine, A.D. 6. So many discoveries about ancient times, concerning which history has been silent, have been made during the last thirty years that it is surprising modern authors should brush aside a statement of St. Luke's, a respectable first-century writer, with a mereappeal to the silence of history on the matter.

(2) The first census in Palestine, as described by St. Luke, was not made according to Roman, but Jewish, methods. St. Luke, who travelled so much, could not be ignorant of the Roman system, and his description deliberately excludes it. The Romans did not run counter to the feelings of provincials more than they could help. Jews, who were proud of being able to prove their descent, would have no objection to the enrolling described in Luke 2. Schürer's arguments are vitiated throughout by the supposition that the census mentioned by St. Luke could be made only for taxation purposes. His discussion of imperial taxation learned but beside the mark (cf. the practice in Egypt). It was to the advantage of Augustus to know the number of possible enemies in Palestine, in case of revolt.

(3) King Herod was not as independent as he is described for controversial purposes. A few years before Herod's death Augustus wrote to him. Josephus, "Ant.", XVI, ix., 3, has: "Cæsar [Augustus] . . . grew very angry, and wrote to Herod sharply. The sum of his epistle was this, that whereas of old he used him as a friend, he should now use him as his subject." It was after this that Herod was asked to number his people. That some such enrolling took place we gather from a passing remark of Josephus, "Ant.", XVII, ii, 4, "Accordingly, when all the people of the Jews gave assurance of their good will to Cæsar [Augustus], and to the king's [Herod's] government, these very men [the Pharisees] did not swear, being above six thousand." The best scholars think they were asked to swear allegiance to Augustus.

(4) It is said there was no room for Quirinius, in Syria, before the death of Herod in 4 B.C. C. Sentius Saturninus was governor there from 9-6 B.C.; and Quintilius Varus, from 6 B.C. till after the death of Herod. But in turbulent provinces there were sometimes times two Roman officials of equal standing. In the time of Caligula the administration of Africa was divided in such a way that the military power, with the foreign policy, was under the control of the lieutenant of the emperor, who could be called a hegemon (as in St. Luke), while the internal affairs were under the ordinary proconsul. The same position was held by Vespasian when he conducted the war in Palestine, which belonged to the province of Syria--a province governed by an officer of equal rank. Josephus speaks of Volumnius as being Kaisaros hegemon, together with C. Sentius Saturninus, in Syria (9-6 B.C.): "There was a hearing before Saturninus and Volumnius, who were then the presidents of Syria" (Ant., XVI, ix, 1). He is called procurator in "Bel. Jud.", I, xxvii, 1, 2. Corbulo commanded the armies of Syria against the Parthians, while Quadratus and Gallus were successively governors of Syria. Though Josephus speaks of Gallus, he knows nothing of Corbulo; but he was there nevertheless (Mommsen, "Röm. Gesch.", V, 382). A similar position to that of Corbulo must have been held by Quirinius for a few years between 7 and 4 B.C.

The best treatment of the subject is that by Ramsay "Was Christ Born in Bethlehem?" See also the valuable essays of two Catholic writers: Marucchi in "Il Bessarione" (Rome, 1897); Bour, "L'lnscription de Quirinius et le Recensement de S. Luc" (Rome, 1897). Vigouroux, "Le N. T. et les Découvertes Modernes" (Paris, 1890), has a good deal of useful information. It has been suggested that Quirinius is a copyist's error for Quintilius (Varus). Saint Luke and Josephus

The attempt to prove that St. Luke used Josephus (but inaccurately) has completely broken down. Belser successfully refutes Krenkel in "Theol. Quartalschrift", 1895, 1896. The differences can be explained only on the supposition of entire independence. The resemblances are sufficiently accounted for by the use of the Septuagint and the common literary Greek of the time by both. See Bebb and Headlam in Hast., "Dict. of the Bible", s. vv. "Luke, Gospel" and "Acts of the Apostles", respectively. Schürer (Zeit. für W. Th., 1876) brushes aside the opinion that St. Luke read Josephus. When Acts is compared with the Septuagint and Josephus, there is convincing evidence that Josephus was not the source from which the writer of Acts derived his knowledge of Jewish history. There are numerous verbal and other coincidences with the Septuagint (Cross in "Expository Times", XI, 5:38, against Schmiedel and the exploded author of "Sup. Religion"). St. Luke did not get his names from Josephus, as contended by this last writer, thereby making the whole history a concoction. Wright in his "Some New Test. Problems" gives the names of fifty persons mentioned in St. Luke's Gospel. Thirty-two are common to the other two Synoptics, and therefore not taken from Josephus. Only five of the remaining eighteen are found in him, namely, Augustus Cæsar, Tiberius, Lysanias, Quirinius, and Annas. As Annas is always called Ananus in Josephus, the name was evidently not taken from him. This is corroborated by the way the Gospel speaks of Caiphas. St. Luke's employment of the other four names shows no connection with the Jewish historian. The mention of numerous countries, cities, and islands in Acts shows complete independence of the latter writer. St. Luke's preface bears a much closer resemblance to those of Greek medical writers than to that of Josephus. The absurdity of concluding that St. Luke must necessarily be wrong when not in agreement with Josephus is apparent when we remember the frequent contradictions and blunders in the latter writer. Appendix: Biblical Commission decisions

The following answers to questions about this Gospel, and that of St. Mark, were issued, 26 June, 1913, by the Biblical Commission. That Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, and Luke, a doctor, the assistant and companion of Paul, are really the authors of the Gospels respectively attributed to them is clear from Tradition, the testimonies of the Fathers and ecclesiastical writers, by quotations in their writings, the usage of early heretics, by versions of the New Testament in the most ancient and common manuscripts, and by intrinsic evidence in the text of the Sacred Books. The reasons adduced by some critics against Mark's authorship of the last twelve versicles of his Gospel (xvi, 9-20) do not prove that these versicles are not inspired or canonical, or that Mark is not their author. It is not lawful to doubt of the inspiration and canonicity of the narratives of Luke on the infancy of Christ (i-ii), on the apparition of the Angel and of the bloody sweat (xxii, 43-44); nor can it be proved that these narratives do not belong to the genuine Gospel of Luke.

The very few exceptional documents attributing the Magnificat to Elizabeth and not to the Blessed Virgin should not prevail against the testimony of nearly all the codices of the original Greek and of the versions, the interpretation required by the context, the mind of the Virgin herself, and the constant tradition of the Church.

It is according to most ancient and constant tradition that after Matthew, Mark wrote his Gospel second and Luke third; though it may be held that the second and third Gospels were composed before the Greek version of the first Gospel. It is not lawful to put the date of the Gospels of Mark and Luke as late as the destruction of Jerusalem or after the siege had begun. The Gospel of Luke preceded his Acts of the Apostles, and was therefore composed before the end of the Roman imprisonment, when the Acts was finished (Acts 28:30-31). In view of Tradition and of internal evidence it cannot be doubted that Mark wrote according to the preaching of Peter, and Luke according to that of Paul, and that both had at their disposal other trustworthy sources, oral or written.

Here followeth of S. Luke the Evangelist, and first of his name.

Luke is as much to say as arising or enhancing himself. Or Luke is said of light, he was raising himself from the love of the world, and enhancing into the love of God. And he was also light of the world, for he enlumined the universal world by holy predication, and hereof saith S. Matthew, Mathei quinto: Ye be the light of the world. The light of the world is the sun, and that light hath height in his seat or siege. And hereof saith Ecclesiasticus the twenty-sixth chapter: The sun rising in the world is in the right high things of God, he hath delight in beholding. And as it is said Ecclesiastes undecimo: The light of the sun is sweet, and it is delightable to the eyes to see the sun. He hath swiftness in his moving as it is said in the Second Book of Esdras the fourth chapter. The earth is great and the heaven is high and the course of the sun is swift, and hath profit in effect, for after the philosopher, man engendereth man, and the sun. And thus Luke had highness by the love of things celestial, delectable by sweet conversation, swiftness by fervent predication and utility, and profit by conscription and writing of his doctrine.

Of S. Luke Evangelist.

Luke was of the nation of Syria, and Antiochian by art of medicine, and after some he was one of seventy-two disciples of our Lord. S. Jerome saith that he was disciple of the apostles and not of our Lord, and the gloss upon the twenty-fifth chapter of the Book of Exodus signifieth that he joined not to our Lord when he preached, but he came to the faith after his resurrection. But it is more to be holden that he was none of the seventy-two disciples, though some hold opinion that he was one. But he was of right great perfection of life, and much well ordained as toward God, and as touching his neighbour, as touching himself, and as touching his office. And in sign of these four manners of ordinances he was described to have four faces, that is to wit, the face of a man, the face of a lion, the face of an ox and the face of an eagle, and each of these beasts had four faces and four wings, as it is said in Ezechiel the first chapter. And because it may the better be seen, let us imagine some beast that hath his head four square, and in every square a face, so that the face of a man be tofore, and on the right side the face of the lion, and on the left side the face of the ox, and behind the face of the eagle, and because that the face of the eagle appeared above the other for the length of the neck, therefore it is said that this face was above, and each of these four had four pens. For when every beast was quadrate as we may imagine, in a quadrate be four corners, and every corner was a pen. By these four beasts, after that saints say, be signified the four evangelists, of whom each of them had four faces in writing, that is to wit, of humanity, of the passion, of the resurrection, and of the divinity. How be it these things be singularly to singular, for after S. Jerome, Matthew is signified in the man, for he was singularly moved to speak of the humanity of our Lord. Luke was figured in the ox, for he devised about the priesthood of .Jesu Christ. Mark was figured in the lion, for he wrote more clearly of the resurrection. For as some say, the fawns of the lion be as they were dead unto the third day, but by the braying of the lion they been raised at the third day, and therefore he began in the cry of predication. John is figured as an eagle, which fleeth highest of the four, for he wrote of the divinity of Jesu Christ. For in him be written four things. He was a man born of the virgin, he was an ox in his passion, a lion in his resurrection, and an eagle in his ascension. And by these four faces it is well showed that Luke was rightfully ordained in these four manners. For by the face of a man it is showed that he was rightfully ordained as touching his neighbour, how he ought by reason teach him, draw him by debonairly, and nourish him by liberality, for a man is a beast reasonable, debonair, and liberal. By the face of an eagle it is showed that he was rightfully ordained as touching God, for in him the eye of understanding beheld God by contemplation, and the eye of his desire was to him by thought or effect, and old age was put away by new conversation. The eagle is of sharp sight, so that he beholdeth well, without moving of his eye, the ray of the sun, and when he is marvellous high in the air he seeth well the small fishes in the sea. He hath also his beak much crooked, so that he is let to take his meat, he sharpeth it and whetteth it against a stone, and maketh it convenable to the usage of his feeding. And when he is roasted by the hot sun, he throweth himself down by great force into a fountain, and taketh away his old age by the heat of the sun, and changeth his feathers, and taketh away the darkness of his eyes. By the face of the lion it is showed how he was ordained as touching himself.

For he had noblesse by honesty of manners and holy conversation, he had subtlety for to eschew the Iying in wait for his enemies, and he had sufferance for to have pity on them that were tormented by affliction. The lion is a noble beast, for he is king of beasts. He is subtle, he defaceth his traces and steps with his tail when he fleeth, so that he shall not be found; he is suffering, for he suffereth the quartan. By the face of an ox it is showed how he was ordained as touching his office, that was to write the gospel. For he proceeded morally, that is to say by morality, that he began from the nativity and childhood of Jesu Christ, and so proceeded little and little unto his last consummation. He began discreetly, and that was after other two evangelists, that if they had left any thing he should write it, and that which they had suffciently said he should leave. He was well mannered, that is to say well learned and induced in the sacrifices and works of the temple, as it appeareth in the beginning, in the middle, and in the end. The ox is a moral beast and hath his foot cloven, by which is discretion understood, and it is a beast sacrificeable. And truly, how that Luke was ordained in the four things, it is better showed in the ordinance of his life. First, as touching his ordinance unto God. After S. Bernard, he was ordained in three manners, that is by affection and desire, by thought and intention. The affection ought to be holy, the thought clean, and intention rightful. He had the affection holy, for he was full of the Holy Ghost, like as Jerome saith in his prologue upon Luke: He went into Bethany full of the Holy Ghost. Secondly, he had a clean thought, for he was a virgin both in body and mind, in which is noted cleanness of thought. Thirdly, he had rightful intention, for in all things that he did he sought the honour of God. And of these two last things it is said in the prologue upon the Acts of the Apostles: He was without sin and abode in virginity, and this is touching the cleanness of thought. He loved best to serve our Lord, that is to the honour of our Lord, this is as touching the rightful intention. Fourthly, he was ordained as touching his neighbour. We be ordained to our neighbour when we do that we ought to do. After Richard of S.Victor, there be three things that we owe to our neighbour, that is our power, our knowledge, and our wild, and let the fourth be put to, that is all that we may do. Our power in helping him, our knowledge in counselling him, our will in his desires, and our deeds in services. As touching to these four, S. Luke was ordained, for he gave first to his neighbour his power in aiding and obsequies, and that appeareth by that he was joined to Paul in his tribulations and would not depart from him, but was helping him in his preachings, like as it is written in the second epistle of Paul in the fourth chapter to Timothy, saying: Luke is only with me. In that he saith, only with me, it signifieth that he was a helper, as that he gave to him comfort and aid, and in that he said only, it signifieth that he joined to him firmly. And he said in the eighth chapter to the II Corinthians: He is not alone, but he is ordained of the churches to be fellow of our pilgrimage. Secondly, he gave his knowledge to his neighbour in counsels. He gave then his knowledge to his neighbour when he wrote to his neighbours the doctrine of the apostles, and of the gospel that he knew. And hereof he beareth himself witness in his prologue; saying: It is mine advice, and I assent, good Theophilus, to write to thee, right well of the beginning by order, so that thou know the truth of the words of which thou art taught. And it appeareth well that he gave his knowledge in counsels to his neighbours, by the words that Jerome saith in his prologue, that is to wit, that his words be medicine unto a sick soul.

Thirdly, he gave his will unto the desires of his neighbour, and that appeareth by that, that he desireth that they should have health perdurable, like as Paul saith to the Colossians: Luke the leech saluteth you; that is to say, Think ye to have health perdurable, for he desireth it to you. Fourthly, he gave to his neighbour his deed in their services. And it appeareth by that that he supposed that our Lord had been a strange man, and he received him into his house and did to him all the service of charity, for he was fellow to Cleophas when they went to Emmaus, as some say. And Gregory saith in his Morals, that Ambrose saith it was another, of whom he nameth the name. Thirdly, he was well ordained as touching himself. And after S. Bernard, three things there be that ordain a man right well as touching himself, and maketh him holy, that is to live soberly, and rightful labour, and a debonair wit. And after S. Bernard each of these three is divided into three, that is, to live soberly, if we live companionably, continently, and humbly. Rightful work is, if he be rightful, discreet, and fruitful. Rightful by good intention, discreet by measure, and fruitful by edification. The wit is debonair, when our faith feeleth God to be sovereign good, so that by his puissance we believe that our infirmity be holpen by his power, our ignorance be corrected by his wisdom, and that our wickedness be defaced by his bounty. And thus saith Bernard: In all these things was S. Luke well ordained. He had, first, sober living in treble manner, for he lived continently. For as S. Jerome witnesseth of him in the prologue upon Luke, he had never wife ne children. He lived companionably, and that is signified of him, where it is said of him and Cleophas in the opinion aforesaid: Two disciples went that same day, etc. Fellowship is signified in that he saith, two disciples, that is to say, well mannered. Thirdly he lived humbly, of which humility is showed of that he expressed the name of his fellow Cleophas and spake not of his own name. And after the opinion of some, Luke named not his name for meekness. Secondly, he had rightful work and deed, and his work was rightful by intention, and that is signified in his collect where it is said: Qui crucis mortificationem jugiter in corpore suo pro tui nominis amore portavit: he bare in his body mortification of his flesh for the love of thy name. He was discreet by temperance, and therefore he was figured in the form of an ox, which hath the foot cloven, by which the virtue of discretion is expressed; he was also fruitful by edification; he was so fruitful to his neighbours that he was holden most dear of all men, wherefore, Ad Colossenses quarto, he was called of the apostle most dearest: Luke the leech saluteth you. Thirdly, he had a meek wit, for he believed and confessed in his gospel, God to be sovereignly mighty, sovereignly wise, and sovereignly good. Of the two first, it is said in the fourth chapter: They all were abashed in his doctrine, for the word of him was in his power. And of the third, it appeareth in the eighteenth chapter, where he saith: There is none good but God alone. Fourthly, and last, he was right well ordained as touching his office, the which was to write the gospel, and in this appeareth that he was ordained because that the said gospel is ennoblished with much truth, it is full of much profit, it is embellished with much honesty and authorised by great authority. It is first ennoblished with much truth. For there be three truths, that is of life, of righteousness, and of doctrine. Truth of life is concordance of the hand to the tongue, truth of righteousness is concordance of the sentence to the cause, and truth of doctrine is concordance of the thing to the understanding, and the gospel is ennoblished by this treble verity and this treble verity is showed in the gospel. For Luke showeth that Jesu Christ had in him this treble verity, and that he taught it to others, and showeth that God had this truth by the witness of his adversaries. And that saith he in the twenty seventh chapter: Master, we know well that thou art true, and teachest and sayest rightfully that is the verity of the doctrine, but thou teachest in truth the way of God, that is the truth of life, for good life is the way of God. Secondly, he showeth in his gospel that Jesu Christ taught this treble truth. First, he taught the truth of life, the which is in keeping the commandments of God, whereof it is said: Thou shalt love thy Lord God, do that and thou shalt live. And when a Pharisee demanded our Lord: What shall I do for to possess the everlasting life? He said: Knowest thou not the commandments? Thou shalt not slay, thou shalt do no theft, ne thou shalt do no adultery? Secondly, there is taught the verity of doctrine, wherefore he said to some that perverted this truth, the eleventh chapter: Woe be to you Pharisees, that tithe the people, et cetera, and pass over the judgment and charity of God. Also in the same: Woe be to you wise men of law, which have taken the key of science. Thirdly, is taught the truth of righteousness, where it is said: Yield ye that longeth to the emperor, and that ye owe to God, to God. And he saith the nineteenth chapter: They that be my enemies and will not that I reign upon them, bring them hither and slay them tofore me. And he saith in the thirteenth chapter, where he speaketh of the doom, that he shall say to them that be reproved: Depart from me, ye that have done wickedness. Secondly, his gospel is full of much profit, whereof Paul and himself write that he was a leech or a physician, wherefore in his gospel it is signified that he made ready for us medicine most profitable. There is treble medicine, curing, preserving, and amending. And this treble medicine showeth S. Luke in his gospel that, the leech celestial hath made ready. The medicine curing is that which cureth the malady, and that is penance, which taketh away all maladies spiritual. And this medicine saith he that the celestial leech hath made ready for us when he saith: Heal ye them that be contrite of heart, and preach ye to the caitiffs the remission of sins. And in the fifth chapter he saith: I am not come to call the just and true men, but the sinners to penance. The medicine amending is that which encreaseth health, and that is the observation of counsel, for good counsel maketh a man better and more perfect. This medicine showeth us the heavenly leech when he saith in the eighteenth chapter: Sell all that ever thou hast and give to poor men. The medicine preservative is that which preserveth from falling, and this is the eschewing of the occasions to sin, and from evil company. And this medicine showeth to us the heavenly leech when he saith in the twelfth chapter: Keep you from the meat of the Pharisees, and there he teacheth us to eschew the company of shrews and evil men.